Ivory Coast: National History through Colonialism and Independence

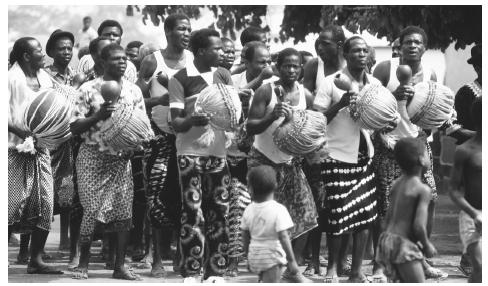

Pre-Colonial Era

Before European colonization, the area now known as Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) was home to various indigenous kingdoms and ethnic groups, such as the Akan, Guro, and Senufo. These societies engaged in agriculture, trade, and local governance systems. The region was rich in culture, with well-established social and political structures.

The Bono kingdom of Gyaman was established in the 17th century by the Abron, an Akan group escaping the expanding Ashanti Empire in Ghana. They settled south of Bondoukou and gradually dominated the Juula, recent migrants from Begho. Bondoukou became a significant center of commerce and Islam, with its Quranic scholars attracting students from across West Africa.

In the mid-18th century, other Akan groups also fleeing the Ashanti Empire founded new settlements in east-central Ivory Coast. These included the Baoulé kingdom at Sakasso and the Agni kingdoms of Indénié and Sanwi. The Baoulé established a highly centralized political structure under three successive rulers but eventually fragmented into smaller chiefdoms. Despite this, the Baoulé resisted French colonization. The Agni kingdoms, particularly Sanwi, sought to maintain their distinct identity even after Ivory Coast’s independence, with the Sanwi attempting to secede as late as 1969.

Arrival of Europeans

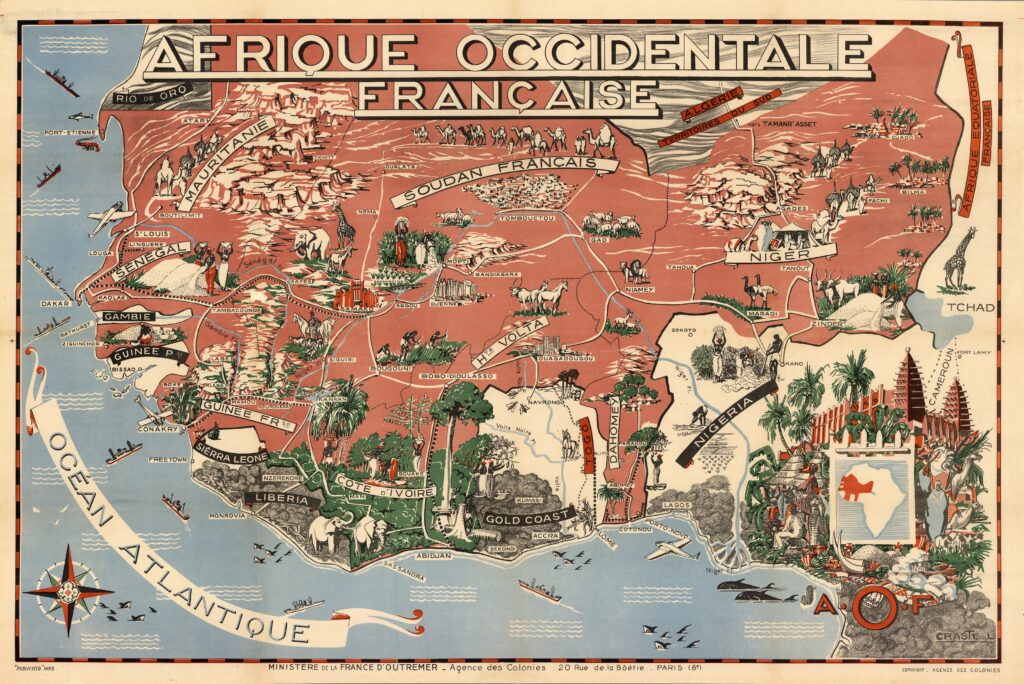

In the 15th century, Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to reach the Ivory Coast. However, it was not until the late 19th century that the French established a more significant presence. France, seeking to expand its colonial empire in Africa, signed treaties with local chiefs, leading to the establishment of a protectorate in 1843. By 1893, Côte d’Ivoire became a French colony, integrated into French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française, AOF).

Colonial Rule

Under French colonial rule, the Ivory Coast experienced significant economic and social transformations. The French focused on developing infrastructure, such as roads and railways, to facilitate the export of cash crops like coffee, cocoa, and palm oil. The colonial administration also introduced Western education and Christianity, which had profound impacts on Ivorian society.

However, colonial rule was marked by exploitation and oppression. The French imposed forced labor, heavy taxation, and land expropriation, which led to widespread resentment among Ivorians. The colonial period also saw the rise of an educated elite, who would later play a crucial role in the struggle for independence.

Ivory Coast officially became a French colony on March 10, 1893. Louis Gustave Binger, an explorer of the Gold Coast frontier, was appointed the first governor. He negotiated boundary treaties with Liberia and Britain. French military contingents established new posts inland, encountering resistance from locals despite protection treaties. The greatest resistance came from Samori Touré, who had founded the Wassoulou Empire, covering parts of present-day Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast. Touré’s well-equipped army posed a significant challenge to French expansion until his capture in 1898.

In 1900, France imposed a head tax to fund public works in the colony, sparking several revolts. The French exploited natural resources and imposed a forced labor system, requiring each adult male Ivorian to work ten days a year without compensation. This system, deeply resented by the African population, was also detrimental to Ivorian farmers. During World War II, European farmers were given labor preferences, while African farmers struggled to find voluntary workers. The labor demands were so high that in 1932, part of Upper Volta was annexed to Ivory Coast to meet the need. The head tax was seen as a humiliating symbol of submission, violating protectorate treaties.

From 1904 to 1958, Ivory Coast was part of the Federation of French West Africa, a colony and overseas territory under the French Third Republic. Until after World War II, governance was administered from Paris. France’s policy of “association” meant that Africans in Ivory Coast were French subjects without representation. In 1905, France officially abolished slavery in most of French West Africa.

Governor Gabriel Angoulvant, appointed in 1908, believed in forceful conquest for the colony’s development. He sent military expeditions to quell resistance, enforce antislavery laws, and support French trade. Local rulers had to comply with French demands, though the French often disregarded agreements, deporting or interning resistant leaders and establishing a uniform administration.

French colonial policy combined assimilation and association. Assimilation extended French culture, language, laws, and customs, asserting French superiority. The policy of association allowed Africans to preserve customs compatible with French interests. An indigenous elite trained in French administration served as intermediaries between the French and the African population.

Path to Independence

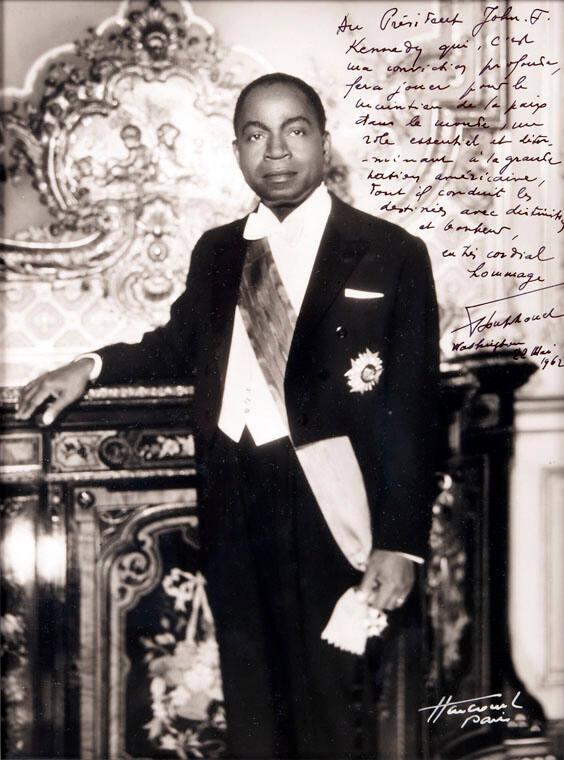

The push for independence gained momentum after World War II. In 1946, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, a prominent Ivorian leader, founded the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI) and became a key figure in the anti-colonial movement. Houphouët-Boigny also played a significant role in the French National Assembly, advocating for the rights of African colonies.

In 1958, Côte d’Ivoire became an autonomous republic within the French Community, a transitional arrangement before full independence. On August 7, 1960, Côte d’Ivoire officially gained independence from France, with Félix Houphouët-Boigny becoming the country’s first president.

Post-Independence Era

Under Houphouët-Boigny’s leadership, Côte d’Ivoire pursued a policy of close cooperation with France and adopted a capitalist economic model. The country experienced rapid economic growth, often referred to as the “Ivorian Miracle,” driven by the export of agricultural products and investment in infrastructure. Houphouët-Boigny’s administration was characterized by political stability, but it also faced criticism for its authoritarian tendencies and lack of political pluralism.

Political Turmoil and Civil War

After Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993, Côte d’Ivoire entered a period of political instability. His successor, Henri Konan Bédié, faced challenges from opposition parties and military factions. In 1999, a military coup led by General Robert Guéï ousted Bédié. The subsequent elections in 2000 saw the rise of Laurent Gbagbo to the presidency.

Tensions between the north, predominantly Muslim and feeling marginalized, and the south, predominantly Christian and economically privileged, culminated in a civil war in 2002. The conflict divided the country until a peace agreement was reached in 2007.

Recent Developments

The 2010 presidential elections led to a violent political crisis when Gbagbo refused to concede defeat to Alassane Ouattara, the internationally recognized winner. The conflict ended in 2011 with Gbagbo’s arrest and Ouattara assuming the presidency. Since then, Côte d’Ivoire has made strides towards reconciliation and economic recovery, although political and ethnic tensions occasionally resurface.

Conclusion

The history of Côte d’Ivoire is marked by a rich pre-colonial heritage, a challenging period of French colonial rule, and a dynamic journey towards independence and nation-building. Despite periods of political instability and conflict, the country continues to work towards stability, economic development, and national unity.